Marine Turtles

Sea turtles have a prominent place among the fauna of the RSA. All five species of sub-tropical sea turtle are known to occur in the Region, where the females come to the beach for nesting. Although turtles nest on the beaches and certain islands of Bahrain, I.R. Iran, Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, three of the turtle nesting locations in Oman are of international significance. Masirah Island has the largest nesting population of Loggerhead turtles, while Ra’s Al-Hadd supports the largest nesting aggregation of Green turtle, Chelonia mydas known in the northern Indian Ocean, and Damaniyat Islands support extensive Hawksbill turtle nesting. Sea bird Sterna spp. and Ghost crab, Ocypode rotundata are the major predators of turtle hatchlings.

Chelonia mydas (Green Sea Turtle)

Milestones

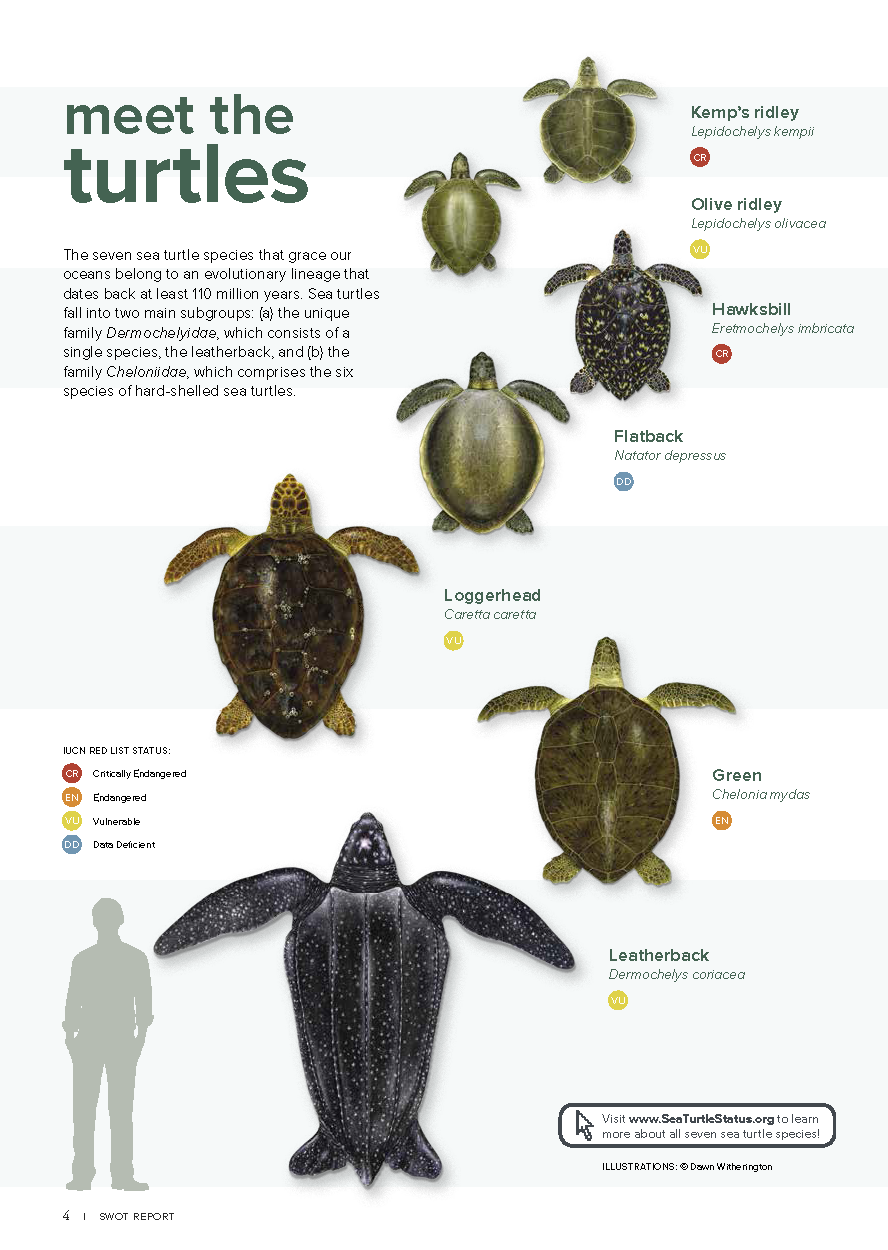

- Five species of turtles are found in the Region, namely, Green turtle (Chelonia mydas), Hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata), Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea), Loggerhead (Caretta caretta) and Olive Ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea)

- Four species of turtles nest in the Region

- Oman plays a host to the greatest number of nesting turtles

- Fishing nets are the major threat to the nesting population

Future Outlook

Carry out a Regional turtle project with the participation of Member States

- A Regional Proposal on Marine Turtle Monitoring and Tagging Program has been submitted from EPA-Kuwait

- Other Member States have also shown interest in joining the Program which has been welcomed by ROPME

- ROPME requested NFP-Kuwait to provide a more detailed project proposal to invite the participation of turtle groups of all concerned Member States in the implementation of this important project

Turtle Nesting Sites in the RSA

Knowing where turtles are in a particular life stage is a critical first step to defining Important Turtle Areas (ITAs), and recent advances in technology are allowing scientists across the planet to begin to unravel many of the mysteries of where turtles go while at sea. One area where this technology was recently applied with great results is the Arabian region, a part of the world not well known for its sea turtles. The study area comprised the RSA. The area supports large green turtle populations in Saudi Arabia and in Oman; smaller nesting aggregations in Iran and Kuwait; and hawksbills nesting in Iran, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Oman is also home to one of the largest loggerhead rookeries in the world, with thousands of nesting loggerheads and a handful of olive ridleys. We know a lot about the nesting populations and a bit about at-sea behavior of olive ridleys and loggerheads, but we know nothing about hawksbill at-sea habitat. That lack is what this study set out to resolve. The Gulf is a unique environment. It undergoes extreme water and air temperature fluctuations, and its climate has a profound effect on sea turtles. Surface waters typically exceed 30ºC (86ºF) for sustained periods, so in many ways the Gulf can be likened to a natural living laboratory for understanding how turtles might adapt to climate change and elevated global temperatures.

The region is also one of the world’s most important exploration and extraction areas for oil and gas, and it has some of the highest shipping traffic in the world. In addition, commercial, artisanal, and recreational fisheries further affect sea turtles, along with endless coastal development. Given those pressures, focused conservation strategies must target the full range and extent of turtles’ life cycles, not just their time on nesting beaches.

Against this backdrop and in partnership with numerous colleagues from many government agencies, the private sector, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), we four were part of a recent project spearheaded by the Emirates Wildlife Society in association with WWF (EWS-WWF) and the Marine Research Foundation, which used satellites to track 75 post-nesting female hawksbills from Iran, Oman, Qatar, and the UAE. Our aim was to identify key foraging grounds, temporal activity patterns, and potential migration bottlenecks, which we deemed to be ITAs. Other project partners provided tracking data of an additional 15 turtles from their own work to supplement the massive dataset we had accumulated. The satellite tracks showed that turtles tended to stay near their nesting sites for varying periods of time, thus allowing us to estimate that they laid between three and six clutches of eggs per season. As they left their nesting grounds, most turtles moved south or southwest toward the corner of the Gulf shared by Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, with only a few traveling into the Gulf of Salwa (between Qatar and Saudi Arabia). Even fewer went northward toward Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Surprisingly, no turtles headed east toward Iran and the eastern reaches of the UAE, an area that receives the cleaner waters entering the Gulf from the Sea of Oman. Outside the Gulf, Omani turtles headed south from the Damaniyat Islands, hugging the coast of Oman, rounding Ras Al Hadd toward foraging sites along the mainland coast between Masirah and Yemen. Masirah turtles were the laziest of all, moving just a few kilometers across to the mainland.

The most important results of this study, though, were the identification of the feeding grounds where turtles spend most of their time. Once they reached their destinations, the Gulf turtles occupied discrete and isolated foraging grounds that are dispersed across a huge swath of the southwest Gulf, then usually returned to the same areas following two- to three-month summer migrations. Their home ranges varied in size but overall were relatively large, averaging some 50 km2 (19 mi2). In contrast, core areas were extremely precise and were limited to individual shallow patches averaging only about 1 km2 (1/3 mi2). Each turtle essentially lived on its own little feeding patch consisting of shallow areas with sparse hard substrate. Omani turtles were different: most of them moved to just a handful of collective feeding areas off Shannah, close to Masirah, and a few went to Quwayrah, approximately 300 km (186 mi) farther south. The Omani turtles’ core areas were also small but were home to numerous turtles, unlike in the Gulf, where turtles were highly dispersed and lived mostly alone.

(Extracted text from the SWOT REPORT, 10th Anniversary Special Edition (2015), by NICOLAS PILCHER, MARINA ANTONOPOULOU, LISA SHRAKE PERRY, and OLIVER KERR, pp. 12-13 with minor edits on the area here referred to as RSA)

Data Description

The data source for the map service is from IBIS – SEAMAP team SWOT – the State of the World’s Sea Turtles Project – is a partnership led by the Oceanic Society and the IUCN Marine Turtle Specialist Group (MTSG), with support from the OBIS-SEAMAP project at the Marine Geospatial Ecology Lab (MGEL), Duke University. This online database and mapping application is built with sea turtle nesting and telemetry data contributed to SWOT since 2004 and also incorporates earlier efforts that produced the WIDECAST nesting database. Since 2012, the data collection and database management are conducted by the OBIS-SEAMAP team at the Marine Geospatial Ecology Lab, Duke University. Currently, SWOT collects data from a network of more than 550 people and projects (SWOT team) for the only comprehensive, global database of sea turtle nesting sites and satellite telemetry data. The SWOT team has provided global nesting locations and satellite telemetry data of all seven marine turtle species: green, leatherback, loggerhead, hawksbill, flatback, olive and Kemp’s ridley. These data have been highlighted here and in annual SWOT reports, available freely in print and online. Furthermore, SWOT supports recommendations for monitoring effort schemes (minimum data standards or MDS) that will allow for comparison of long-term nesting abundance and trend estimates for regional and global populations of sea turtle species.